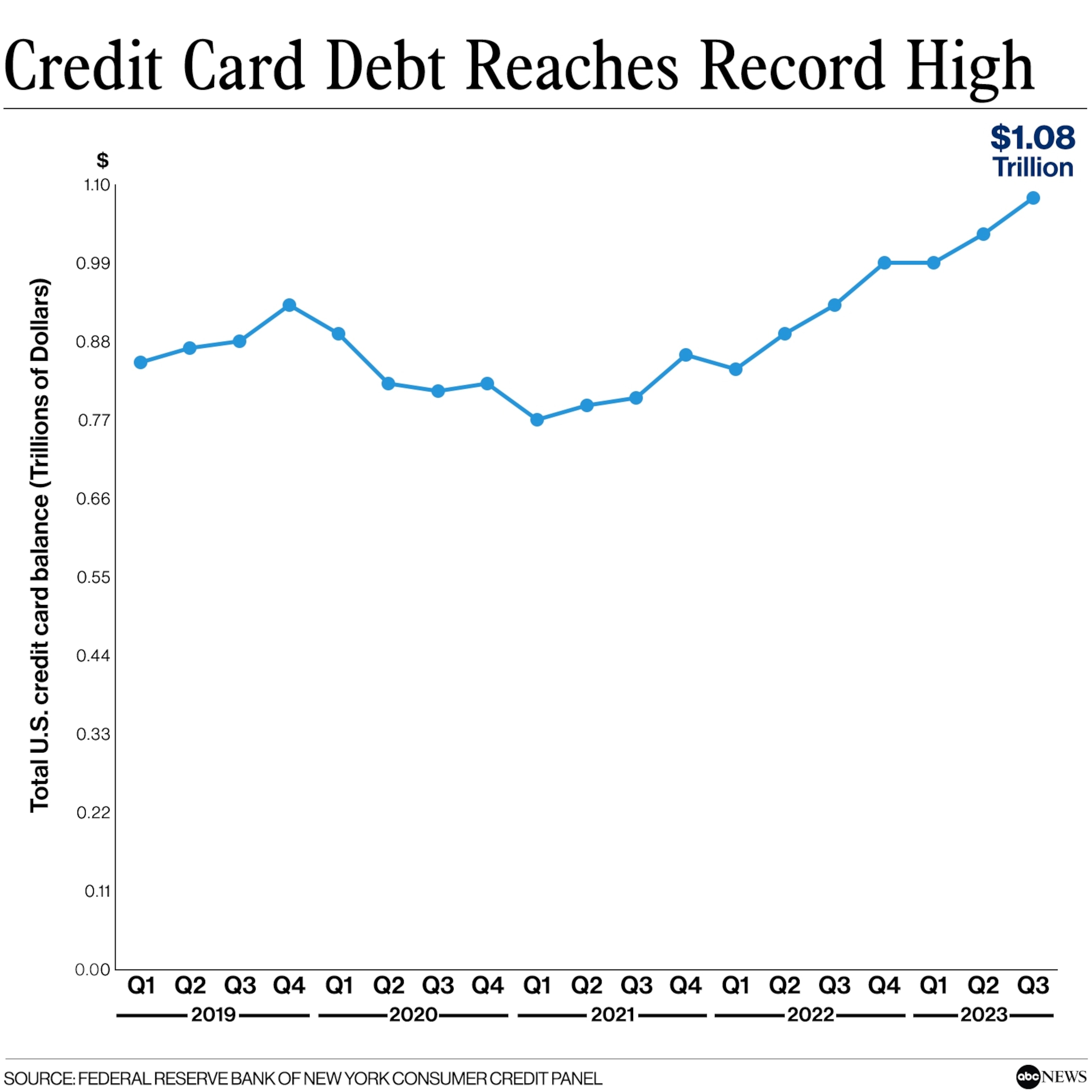

Credit card debt climbed to a record high in the third quarter of 2023, surging nearly 5% from the previous quarter and leaving a growing share of borrowers late on payments, a Federal Reserve report this week showed.

The report demonstrates the dwindling savings held by some consumers who amassed a financial buffer during the pandemic but later burned through it under the strain of rapid price increases, economists told ABC News.

The financial hardship, they added, has fallen primarily on low-income people squeezed between elevated prices and high interest rates who borrowed money to cover the rising expenses.

The economists differed, however, on the economic implications of the credit card debt. Some treated the data as evidence of an alarming trend that foretells weakness for U.S. consumers and a potential economic slowdown. Others said the debt doesn’t threaten the wider economy.

Here’s what to know about what the record credit card debt means for the economy:

Consumers are spending the savings built up during the pandemic

The Fed report marks the latest indication that some consumers have exhausted savings built up during the pandemic as a means of weathering high prices, economists said.

The average net worth of U.S. households skyrocketed nearly 40% between 2019 and 2022, a rate more than double a previous record high in the early 2000s, the Federal Reserve found last year.

U.S. credit card debt briefly fell during the pandemic but has climbed since 2022

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel

The surge coincided with a rapid rise in prices, however, as inflation reached a peak last summer. In turn, the average savings rate for U.S. households has plummeted since 2022, the Fed said last month.

“We had all-time high household savings and inflation strikes and people have to do something about that,” John Sedunov, a finance professor at Villanova University’s School of Business, told ABC News.

“People have to deal with this somehow,” he added. “After blowing through savings to buy essentials, they do what’s next: Find sources to borrow.”

U.S. consumers, who account for nearly three-quarters of U.S. economic activity, drove breakneck economic growth in recent months, Mary Hansen, an economics professor at American University, told ABC News. The data released this week suggests the consumer spending was fueled in part by debt, she noted.

“Consumer spending, which we all know is the base of GDP, is really being held up by credit card debt and maybe it’s not sustainable,” Hansen said.

In this undated file photo, a woman is shown shopping online.

STOCK PHOTO/Getty Images, FILE

High prices are squeezing low-income people

The jump in credit card debt also indicates that elevated inflation has imposed acute hardship on some low-income people, economists said.

Overall delinquency rates on a range of consumer loans — including credit card, auto and student borrowing — ticked up to 3% over a three-month period ending in September, the Fed report showed.

“The increase in credit card debt and delinquencies reflects in part the increased financial stress on lower-income households, who have been hit hard by the higher cost of living,” Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told ABC News.

Low-income people in financial distress have responded to high prices in part by taking on additional credit card debt. But such loans come with high interest rates that can exacerbate an individual’s budget problems, Hansen said.

Average credit card interest rates stand at nearly 21%, Bankrate found last week. That figure is up from roughly 16% at the outset of 2022.

“It puts people on the low end of the income distribution in a real bind,” Hansen said.

While the difficulty faced by low-income people hold significant implications for their financial outlook, such hardship bears little on the wider economy since low-income people account for a relatively small share of overall consumer spending, Christian Weller, a public policy professor at the University of Massachusetts at Boston, told ABC News.

In contrast with Hansen, Weller said the rise in credit card debt and delinquency falls short of posing a threat to the economy.

“We’ve had really gangbusters consumption,” Weller said. “A lot of this was driven by consumption among upper and middle income households.”

He added, “Those people still have more cash on hand.”